Welcome to our first session this month in The Rehearsal Room with Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya!

As we delve into the world of Anton Chekhov, we find ourselves confronted with the rich emotional tapestry of his characters, particularly in his play Uncle Vanya.

Our session opens with a tribute to Fran Bennett, a beloved actress and voice teacher who had recently passed away (in 2021). This moment of reflection sets the tone for our discussion, reminding us of the impact that art and mentorship can have on our lives and careers.

Throughout the episode, we explore the themes of Uncle Vanya, focusing on the characters’ emotional struggles and the longing for beauty and change. Each actor shares their personal experiences with Chekhov, revealing how these timeless themes resonate with their own lives. They discuss character motivations, the significance of age, and the societal pressures that shape our identities.

One of the standout moments in the episode is when the actors discuss the concept of a midlife crisis, a theme that resonates deeply with Vanya’s character. As he grapples with feelings of inadequacy and the realization that his life has been spent in service to a professor who ultimately disappoints him, we see a reflection of our own struggles with purpose and fulfillment.

The episode also touches on the environmental themes present in Chekhov’s work, particularly through the character of Astrov, who laments the destruction of nature. This commentary feels particularly poignant in today’s world, where environmental concerns are at the forefront of global discussions.

Whether you’re a seasoned actor or a curious audience member, this episode promises to inspire and provoke thought!

What happened in the Week 1 Session?

🏁 In this session, highlights include:

- Exploring Chekhov’s characters and their complex relationships

- Discussing the impact of beauty and its ephemeral nature in the play

- Examining the themes of longing and self-worth that resonate throughout the narrative

Watch the Week 1 Session!

Full transcript included at the bottom of this post.

Subscribe to get notified of our next rehearsal session!

And there’s the audio version too – you still get everything from listening!

Total Running Time: 2:03:00

- Stream by clicking here.

- Download as an MP3 by right-clicking here and choosing “save as/save link as”.

Get the show delivered right to you!

Short on time?

Check out this 80-second clip from this session with Sara and Libby discussing character obstacles!

And a great quote from this week’s session…

References mentioned in the Week 1 Session:

- FIVE CHEKHOV PLAYS: Libby and Allison’s translation of Chekhov

- Anton Chekhov

- Oregon Shakespeare Festival

- Ivanov (play)

- The Cherry Orchard (play)

- Three Sisters (play)

Support The Rehearsal Room on Patreon – get early access to sessions (before they go public on YouTube and the podcast), priority with asking questions, and more!

Thank you to our current patrons at the Co-Star level or higher: Ivar, Joan, Michele, Jim, Magdalen, Claudia, Clif and Jeff!

THE SCENE

Our group will be working on the first half of Act 2.

Follow along with the play here. Order a copy of Libby and Allison’s translation here.

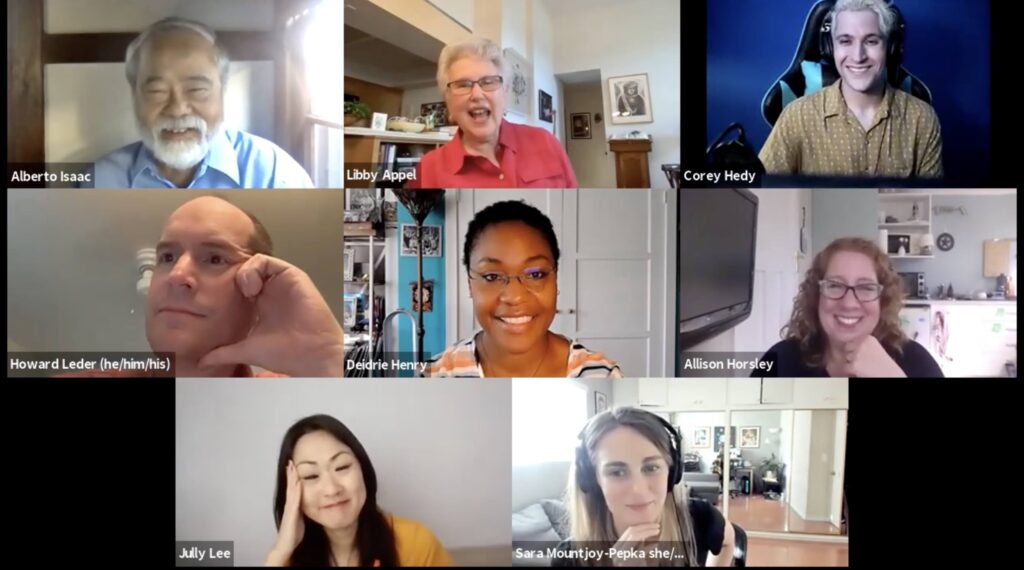

Uncle Vanya Team – with artists in CA, Chicago, and New Zealand!

- DIRECTOR: Libby Appel (Q&A episode)

- VOICE COACH: Ursula Meyer (Q&A episode)

- DRAMATURG: Allison Horsley

- PROFESSOR: Alberto Isaac (episode)

- SONYA: Deidrie Henry

- MARINA: Jully Lee

- VANYA: Howard Leder

- YELENA: Sara Mountjoy-Pepka

- ASTROV: Corey Hedy

Read more about the artists here.

And there’s more!

Catch up on our other workshops featuring lots of Shakespeare scenes, from Hamlet, King Lear, Troilus and Cressida, Midsummer, As You Like It, and our Twelfth Night repertory extravaganza – all on the podcast and YouTube. If you’ve missed any presentations thus far, click here to find them all.

Click here for the transcript!

UNCLE VANYA Week 1 Session: “Love, Loss and Longing” – The Rehearsal Room

Nathan Agin: Yes, here we are officially to start some Chekhov. I’m so thrilled to be back in this rehearsal room. We kind of took the summer off after doing some repertory sessions. Sarah was part of that, in the late spring and it was a lot of fun. and now we’re experimenting with Chekhov. And who better to kick that off with than Libby and Allison? I’m really, really honored that you. You can both be here and Libby from California and Allison from New Zealand, It’s fantastic. So The miracle of this technology. It’s really great. So I just have a couple things that I wanted to do up, front and then I’ll let you guys get underway with rehearsal. we will do a ah, quick intro and all that so everybody can just kind of acclimate and get to know everybody very briefly. but as I mentioned, in the email on Sunday, as some may know, Fran, ah, Bennett transitioned on Saturday. And you know, she was a wonderful, wonderful actress and voice teacher. And I know many on this call, worked with her and knew her for many years. And even if you hadn’t worked with her, you probably admired her work, either from up close or afar. and so I just wanted to take a moment right now and a moment of silence. We’ll just kind of honor Fran’s legacy and contribution to the. The. Thank you for doing that. I will say, as I’m sure many do have, memories and recollections of Fran, perhaps at the end of rehearsal today, if people are feeling so moved to share any of that, you can, Or the Facebook group, that some of you have connected with, you know, is another opportunity. I had been in touch with Fran, you know, via email about potentially involving her in some of these, workshops we were going, that were going on and it would have been just a real honor for her to be part.

Nathan Agin: But we’ll just We’ll always keep her in our thoughts and our hearts. So, But again, thank you for taking that moment with me. So next, what I want to do is just have us go around kind of a quick round robin, and for everybody to introduce yourselves because maybe not everybody knows everybody or has worked with everybody, and just share a little bit about who you are, where you’re coming from, maybe a little bit about your experience with Chekhov and you don’t need to have any experience with Chekhov. That’s what this session is for. but, I’ll start because nobody likes to go first, so I’ll make myself go first. but, my name is Nathan, and, I’ve trained as an actor, worked as an actor, and about a year and a half ago, over, conversations with, professional actors. We created this, series and have just been refining it over time. And it’s been a lot of fun to have this much time to work on the text in this way. and, I personally, I don’t know if I’ve ever. I don’t think I’ve ever done a Chekhov play. I’ve certainly seen, a lot of, Chekhov and scenes and. And all that kind of stuff. But, my. My kind of main acting gig right now is audiobook narration. So that’s. That’s what I do, at night when it’s quiet, and, you know, in the middle of the night, that’s what I do. So, but that’s. That’s what I’m up to. And, how about we turn it over to Libby?

Libby: Oh, I knew you’d do that. First, I want to say, thank you for taking that moment for Fran Bennett. She was beloved and admired and a powerful presence in anyone’s life. Who knew her? Ursula. We worked with her together at CalArts. Do you remember that? Were you there at the time that she was?

Ursula: I never took that job at Cal Arts, but.

Libby: Oh, God, I’ll never forgive you for that.

Ursula: but of course, she’s a Linklater teacher, so I worked her a number of times through the Linklater community, and she. She was very present in this last year since Kristin passed, and so, very dear to all our hearts. Mighty presence. Yeah. And lived a lot longer than it says she did.

Libby: Is that so?

Ursula: She had her 90th birthday a couple years back, but Wikipedia’s clever. Or she was clever.

Libby: Well, she, was an extraordinary woman. Okay. I’m Libby, and I am Brooklyn born. Came, lived in a lot of places in this country. and the one that I lived in the longest in my life was Ashland, Oregon, believe it or not. From Brooklyn, New York, to Ashland, Oregon. That’s quite a journey. I have known and loved Anton Pavlovich since I’m 16 years old. That’s another story. You can ask it sometime. And, so in other words, from New York to Santa Barbara via a lot of other states, I’ve carried the torch for this guy. Somebody just sent me. Did you see this series, of pictures of hot Chekhov? Oh, my God, they’re so fabulous. He was so gorgeous. So I remain in love with him, and we will all discover together why I’m such a crazy person about him.

Nathan Agin: All right, perfect. more to be discovered, with Libby. Alberto.

Alberto: Yeah. Hi, I’m Alberto. I was born in the Philippines. Screw up there.

Libby: where? I’m sorry?

Alberto: Philippines. I was born in the Philippines, and I, grew up there. I, I’ve lived in Los Angeles ever since I moved to the United States. Los Angeles area. haven’t been doing much, Chekhov. I was telling Nathan I did a production of Three Sisters at East West Players in the 70s. I. I played the Baron. Baron Tusenbach.

Libby: Very nice.

Alberto: Yeah, I was younger then. and with the Pandemic, I haven’t done much. I did go off to the Dominican Republic earlier this year to work in a small role with J. Lo in Rom Com. They were filming there.

Libby: Wow.

Alberto: But otherwise, locational, zoom m, reading and so forth.

Nathan Agin: Oh, great.

Alberto: Thrilled to be here.

Nathan Agin: Well, good. Wonderful, wonderful. You can be here. Corey. Hey, everyone.

Corey: I’m Corey. It’s nice to meet you all. I’m from Long Beach, California. I, I studied acting at California State University, Long Beach.

Libby: I used to teach here.

Corey: I read that, and I thought that was awesome.

Libby: Yeah.

Corey: And then that’s where I, did my first Chekhov. I did my first checkoff scene in Hugo Gorman’s. And I met my partner doing, Yelena and Astrov, the map scene.

Libby: And it’s a very sexy scene.

Corey: It sure is. And, yeah, I’m going back to Harry Potter and the Cursed Child in November. And, yeah, that’s about me.

Libby: Awesome.

Nathan Agin: Ah, awesome. Corey.

Howard: Great.

Nathan Agin: You can be here. Deidre.

Deidre: Hi, I am Deidre Henry Dickerman.

Deidre: Since we’re saying we were born, I was born in Barbados and grew up in Atlanta and lived everywhere. and my first, I’m right now in Los Angeles. My first introduction to Chekhov, was 20 years ago playing Irina and three sisters. that was, directed by Libby Apple at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. and it made me fall in love with, these characters, with the story, with their yearning, and with their. There’s just the connection to life that they have. and I am very excited to be working with you guys. So thank you. Thank you.

Nathan Agin: Awesome. Thanks, Adri. Howard.

Howard: Hi, I’m Howard. I’m originally from Redding, California, which is almost like Ashland. Not quite. Not nearly as civilized, maybe.

Howard: I have sort of a dual career. I work as an editor in television. And, have just started acting again about three years ago. Came back to this. And, this summer I’m at Utah Shakes, which has been awesome. My experience with Chekhov is fairly limited. I’ve always been kind of fascinated by the plays when I’ve seen them, and always been like, how. How does that even work? And, I took a class, I guess, at Antaeus probably about a year and a half, two years ago with, With Rob Nagel, where we worked on scenes from these plays, for folks to know him. And that was really kind of my first exposure to playing some of these roles, which was. It was pretty great and left me wanting a lot more. So good to meet you all.

Nathan Agin: Yeah, wonderful. Thanks, Howard. Alison.

Alison: Hi, everybody. I’m Alison Horsley. I’m originally from Tyler, Texas. And, I moved around a lot working in theaters. and I guess more of my history with Chekhov is really because of my history with Russian language and literature, which started on kind of a whim. my first year of college, I decided to take Russian. I thought it would be hard and interesting, and that was true. And after that I was really, I was quite intimidated by Chekhov and really afraid of him until really, Until, Oregon Shakespeare Festival commissioned me to, work with Libby to translate Cherry Orchard for her to direct in her final season at osf. And so I really got to know Chekhov and his work through a combination of, sitting with the plays for a very long time and looking at the language and then also working with Libby and learning how well it can play on its feet. And so it’s been a process for me of really learning about that. So I’m a theater person and a Russian person. but nowadays I live in New Zealand and I don’t do as much Russian. So I’m excited to be back in a room.

Nathan Agin: So maybe you’ll be translating into, like, an indigenous language in New Zealand or something. next.

Alison: Actually, it’s Te Reo, Maori Week here in New Zealand. So everybody is, like, working on beefing up their Maori language, which is what my green sticky notes are in the background. So that’s what that is.

Nathan Agin: I remember being in Barcelona and the local, the country was making an effort to teach people Catalan. So I don’t know, maybe there’ll be something in New Zealand where they Want to make sure that this language, you know, stays active.

Libby: And they should.

Alison: Yeah, very much so. It’s. It’s very. It’s a very active effort.

Libby: Very important that we don’t lose these things.

Nathan Agin: Absolutely. very cool. Well, thank you, Alison, for joining us, from tomorrow from, New Zealand. That’s wonderful. Jully, how about you? Next.

Jully: Yes. Hi, I’m Jully Lee, actor. I spent the Pandemic doing a ton of zoom readings, directing and acting. It’s been a constant stream of doing that. As far as Chekhov. I have, pretty much no experience. I saw my first Chekhov was watching Ivanov at the East Coast Players Conservatory. So it was a student production of Ivanov. I, did a monologue and an acting class for Studio Steven Book. And I did a couple of improv scenes that were based on. On Chekhov genre, based improv. So I have very little exposure, but I’m really, really excited to sink my teeth into this. So thank you for having me.

Nathan Agin: Yeah, absolutely wonderful, Jully. Thank you, Ursula. Oh, you’re still mute. Almost. There you go.

Howard: One second.

Ursula: I have a monitor, so it takes a while. Should we also do my.

Alberto: Of course.

Ursula: Okay, so I’ll go first. Yeah.

Libby: You’re here.

Ursula: You have to introduce yourself. so, ah. I was an actress for a while, and then I became a voice teacher and voice coach. And now I am, heading the graduate acting program at ucsd. I had many lovely years with Libby and Deidre and this guy at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. And, I don’t know that I worked on a check off with you there. I think I might not have. but I worked on 13 Sisters with Diana Lamar and another group, years in that many years. But I taught for four years at JL School of Trauma. And, Carol Gister is a wonderful. Or was a wonderful teacher of, Shakespeare, Chekhov. And so I did a lot of, a lot of coach a lot of the plays and loved them more every time. And they’re just oceans deep and funny. and then I taught a couple times, acting Chekhov at ucsd and we had a glorious time. There’s just no way to get to the bottom of it. And that’s the joy. so, I think I acted in a couple of scenes. I don’t think I’ve ever acted in one of the plays. I remember Clayton Crozet coaching me in a scene in grad school, the Nina Tergoren, scene where she sits and listens. And it was a Beautiful time. So that’s. And here’s my husband, James Newcombe.

Howard: Hi, I’m James Newcomb, and, I’m thrilled to be here and observe this today. And, Libby and I go back to Oregon Shakespeare Festival. we did a Merchant of Venice together and a Richard III together.

Libby: Richard iii. That was pretty spectacular. Jamie, your Richard III will stay in my memory and heart forever.

Howard: Well, and mine as well. It was really, really special. Special, time. I’ve never done any Chekhov at all. I have never been in a scene. I have never been in a Chekhov play. I don’t know how it’s passed by so far. but, it just has never happened. And, you know, the Treplev was a role that I was desperate to play and didn’t have an opportunity to, you know. And now, And, Vanya was one, and I’m past that.

Libby: So, no, I don’t think you.

Howard: Fears. Maybe I’ll die on stage playing fears.

Libby: That’s what every Jacobian actor comes to, fears.

Alberto: Yeah, that’s right.

Nathan Agin: Well, I’m thrilled that, Ursula, ah, you know, is here and Jamie can sit in. And for those who saw Jamie play Silvius and as yous like it earlier this year, Jamie, there may still be time for you to play Vanya or Treple there.

Libby: You know, there’s, not Treplev, but definitely Vanya.

Nathan Agin: Well, in this. I would say in this format, we can always revisit, those two characters. Wonderful. And, Sarah.

Libby: Hi, everyone.

Sarah: So happy to be here. I’m Sarah. I’m from the Seattle region and I’m in Los Angeles. I’ll get to my checkup in a moment, but I want to say, for Libby and you other OSF folks, my first. The first Shakespeare I ever saw was in 2003. It was midsummer at OSF. And it was, It blew my mind, made, me want to go into Shakespeare and play Helena. I’m finally playing Helena this summer. And it’s been this, you know, like a 15 year goal after watching that. And it was also the first theater production I had seen that had color, conscious casting, which also was, very significant for me to be able to see that and helped move things forward. And I just. It was such a great production.

Libby: do you remember who directed it or who played in it?

Sarah: I was in high school, so I didn’t pay attention to things like that. I was just.

Libby: I can’t remember the 2003 was it outdoors?

Sarah: Yeah, it was in the globe. Y Space.

Libby: Yes.

Sarah: Yeah, yeah, it was wonderful.

Libby: It’s wonderful to me that you were so touched by it.

Sarah: Yeah, yeah, it was very, very impactful. so thank you. And, as far as Chekhov goes, I feel like I have some, but not a lot. The first time I read Chekhov’s plays was while I was backpacking across Turkey. And so I sometimes picture these plays with that setting as opposed to the Russian countryside. and then I reread them a few years ago when I took a semester in improvised Chekhov, at a company where Jully and I are actually both company members. so I did six months of fully improvised Chekhov plays, but I have never done a scripted Chekhov scene, which is probably a bit cart before horse. So I feel like I’m catching up now, to learn how this all actually works the way it’s supposed to be done.

Libby: Love it.

Nathan Agin: Awesome.

Howard: That’s great.

Nathan Agin: Well, thank you, Sarah. and, wonderful that, you can join us again. And, you know, Sarah, you mentioned something that has been very important as part of this, and it’s evident in this group today, is that we can be, you know, with this format and with this exploration of just the text and the plays, we, can be very conscious about, age and gender and, all those things, that, you know, we can explore that and explode those concepts and really have fun with, this. So I’m. I’m excited that, we get to do that once again with this group, and just, really thrilled that, you can all be here. And, thank you very much for doing a quick intro. I believe we, got everybody. but, yeah, that’s wonderful. So I will.

Libby: Hello, my name is Joan Saxton.

Ursula: I’m one of the white faces here.

Nathan Agin: Oh, hi, Joan.

Ursula: The screen is telling me that you.

Libby: Have my video blocked. Is that true? Yes.

Nathan Agin: So just for the audience members, we typically have people off camera and just on mute, so you can observe. And if there’s, you know, opportunity at the end for questions, you know, we can, you know, if there’s time, we can look at that, but otherwise, it’s just kind of a fly, on the wall experience.

Libby: Okay, that’s fine with me. But I’d like to say just one thing to another member here. Are you the Jamie that jumped over.

Ursula: The casket when you began Richard iii?

Libby: No. No.

Nathan Agin: Did you. Did you guys are muted?

Howard: No, no, I didn’t jump over a casket. it started with me upstage in a ball. And then one crutch came out, another crutch came out, and then pulled myself, turned around and came down to the stage.

Libby: Okay, thank you.

Nathan Agin: Yep. Okay, cool. All right, well, with that all, everything taken care of, I am going to turn it over to Libby. if you guys have any questions or anything, you can. You can drop a note in the chat. I’ll just be. I’ll be another fly on the wall. but, just excited to listen in and hope you have a wonderful afternoon.

Libby: Thank you. Well, it’s great to start, and I was glad to hear, that some of you had glancing relationship with, Chekhov. I, know that every actor you’ve ever known who’s done a Chekhov has probably said to you, oh, it’s so great. It’s so great. And it is. It’s actors territory. It’s the stuff that actors love. Also may seem like Shakespeare at first because the language is so demanding. that check of how do I approach it? How do I do it? I mean, is it, you know, just. It’s too hard. It only belongs to, the great actors of the world. Well, of course, Checklist belongs to everybody. And, we’re gonna try to find our way in it. I just want to say this format is a little overwhelming for me. I have participated in watching Zoom, and I’ve had some family Zooms, but I’ve never done a class with Zoom. And I tend to, comment when people are talking because I get excited about what you’re saying. And you have to forgive me if I’m interfering with your comment. I never mean to be. And, we’ll just have to figure out how to work together. The other thing to say is that I work mostly by questions. I’m going to ask you a jillion questions, and I think it’s actually going to be you that’s going to tell us how to play these roles by the time we finished in another three weeks. so I have no answers. I only have what I have discovered personally. And each one of you is going to discover for yourself what’s going on here. That’s why Chekhov is so great, because it’s for you, whoever you are, wherever you are, whether you’re in tomorrow or today, it’s material that, is true. I’m just reading right now, a book by Maggie O’Farrell. I don’t know if any of you have caught on to her. She just wrote Hamnet. I mean, she wrote Hamnet, which is an exquisite book. And I’ve been just going through all of her books, and I keep saying, how Jacobian. How Jacobian. Because she really understands the human heart. And she speaks of it. She writes, of it in a way that’s just small details and stupid little incidents. And everything is revealed to you in your heart about what’s going on with these characters. It’s so divine to find that, when that happens. So you’ve had a little glancing. Deidre is, I think, the only one here who’s played a whole role then. Is that right? Yeah. and the discovery process. You don’t have to say yes to this, Deidre, but I’ll be disappointed if you don’t. The discovery process through throughout the rehearsals is pretty fantastic, isn’t it? Personal discovery?

Deidre: Absolutely. Absolutely. Because it just. It’s sort of. It sits on your soul.

Deidre: It sits right. Right on the. Right on the edge of where it allows you to go wherever you need to go.

Libby: Yeah.

Deidre: You know, which I thought was really beautiful about it. and it was unexpected because reading it is very different than playing it, reading it. You know, I found myself sort of,

Deidre: Making them somewhat absurd, if that makes any sense, you know.

Libby: No, he’s looking for you to do that.

Deidre: Yeah. You know, and then. But then when you play it, there’s. There’s a certain place that it sits in you, where you understand there. You understand where they are. You understand how they feel. You understand what. The yearning, you know?

Libby: I love you using that word, yearning, which you did before, too.

Deidre: Yeah. and it sits right there on the surface of that. and I think that’s why I fell in love with it so much, was that it was difficult language, but it was easy to access, if that makes sense.

Libby: Of course, we did. The three sisters before Alison and I began the process of translating, the five plays. so I feel like, wait a minute. Let’s do it again. I want you to wait until you do it again with these translations. Because I think these translations are a little bit more alive than the ones that I used before. Alison and I just. It was a kind of amazing coming, together, wasn’t it, Alison? you were a little scared. I was scared. I spent my life reading and directing and playing, Chekhov’s plays and scenes and all of the short stories and the letters and our mutual darling friend Louis. Doubt that said Libby. This is your final checkup for the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. you should translate. it Yourself. I said, translate myself. I was too scared. Couldn’t begin to do it. I didn’t speak any Russian. and she said, I’m going to find you a Russian translator. And she found me, Allison. And it was such a magic combination, wasn’t it?

Deidre: Oh, yeah.

Libby: Well.

Alison: And I met you. I only met you. I interned at Oregon Shakespeare Festival. And I didn’t meet you because, you were running out the front of the building because you had a grandbaby that was being born. And that was the last I saw of you, was you flying out the front of the building.

Deidre: Well, I’ve got four of them now, so.

Libby: Yeah. What year was that, Allison?

Alison: That was 1997.

Libby: My first. Yeah, he’s 23 now.

Alison: We’re so old. Yeah, it was magical. I think we gave each other permission to really learn the language.

Libby: Exactly. In fact, let me just tell this one little side story. the first one was Cherry Orchard. Because I wanted to do Shakespeare’s. In my final season, as artistic director, I wanted to do a, Shakespeare in his final play, the Tempest. I know there’s question whether that’s final or not, but it was final for me. And, Cherry Orchard, Cecco’s final play. And, I had the opportunity to choose these and do them myself. And the idea of me translating was just beyond possibility. I forgot where that story was going. Okay, I’ll leave it alone and come back to it. I want to know. I asked you all to read the whole play, Uncle Vanya, because it’s impossible to do the scene without knowing where it’s coming from and where it’s going. And I want to get from you, your. What your feelings were in reading it. and I want your honest feelings. I don’t want you to hold back, and I don’t want you to think that you need to sound a certain way. I need you to be really honest with me about what you discovered as you read it, even if you hated it. Anybody take up the.

Corey: Yeah, I’ll go.

Corey: I really loved it. I thought it was very, very sad. all the characters are very sad. it seems that there’s a huge desire for change or something new. obviously, everybody’s bored and everybody has nothing to do.

Libby: And.

Corey: Or this. This longing for beauty, for beauty in the world, for beauty in their atmosphere, for beauty all around. And it seems to just get flip flopped, back and forth whether, I don’t know, Astro’s talking about trees and you can feel that he feels this certain way and I mean, Yelena talking about how bored she is all the time, and everybody’s so annoyed by her, I guess, in that way. I just. I thought it was very, very beautiful. Beautifully written. I loved it.

Libby: I love those things. Yes. Anybody else have first impressions of it?

Howard: This go round for me was like, I’ve always had a hard time reading Chekhov because especially in the first act or two, so much is unsaid, I guess, or like deliberately unsaid. I think particularly in this play where there’s sort of this dam that breaks all at once in the third act. And I was like. I suddenly had this, like, thought. I was like, you almost have to kind of. Though you can’t really read it backwards. You have to kind of read it backwards, you, know, like. Like knowing where they get to so that you can see all the things that. All the tensions that are boiling under the surface in the first act or two of most of these plays. And for me, I don’t know that kind of. I also thought the translation was really beautiful and I found. I also thought the ending was really, really moving. but for me, it was like the first time where I wasn’t just going, how do you play this? But I was like. I was like, oh, this is kind of an amazingly constructed play. I never had that experience before. I often found Chekhov m. Boring to read.

Libby: People mostly say,

Howard: And then this time through, I think maybe I had more experience with it, or I’m just a different person reading it. But. But I was like. I was like, oh, there’s. There. They’re not saying things. And that’s what’s maybe important as. As important as the stuff they are saying.

Libby: Great, wonderful observations, Howard. Other people. Let me hear what you think.

Jully: Yeah. It felt like they were not saying so much and yet saying a lot as well. With the history and the relationships between the characters just saying it point blank, like who this person is and what their histories were. I thought that was interesting. It felt a little, belabored at first when I was first reading it, but it definitely places things in context. What really struck me was its, Relevance.

Libby: Yes, it.

Alison: It’s.

Jully: It’s mind blowingly relevant and I can’t imagine a time.

Libby: Right. Sadly relevantly relevant.

Jully: But I was thinking in history, and there’s not really a time in life where this isn’t relevant. Yeah, it kind of blew my mind how this writing did that especially. Especially. But, you know, especially now in 2020, this constant. It’s just people want change, but it’s just impossible.

Libby: There’s.

Jully: There’s no out. And, it very much affected me in that.

Libby: And we’re cutting down the forest and. And the climate is changing and everything he talks about. And do you remember that he says in a. In 100 or 200 years, it’ll be different. And of course, it’s over 100 years later, and it’s, worse. Way worse. Yeah.

Jully: Yeah. Tragic.

Libby: Tragic is right. Yes. Other thoughts? Other impressions, Dage? Yeah.

Alberto: I’m sorry.

Deidre: Well, I remembered, just that same, you know, that the world will be better in 200 years. I remembered that from, three sisters. So that was really moving. But I also realized there were parts of it that were really funny.

Libby: Like.

Deidre: Like, they’re like. For some reason I forgot the humor. And I don’t know if it was because it was the second reading, you know, the first reading, I was like, oh, God, they’re just so extreme. and, you know, just. But then the second time I read it through, I really, like, the humor really came out for me, where I wasn’t laughing at their absurdity. I was just laughing at just their house. How, Not just sincere, they were, But earnest. They were. And I just thought, remember.

Libby: Do you remember any parts that were particularly funny to you? I’m putting you on the spot. I don’t mean to.

Deidre: Yeah, you’re putting me on the spot. let me see if I can find it. I’ll find it.

Libby: Okay. Okay.

Sarah: Good weather for a hanging.

Libby: Sorry?

Sarah: Good weather to hang yourself.

Libby: Yes. Good. Good. Yes. Yes. That’s good.

Alberto: Alberto, said my. My point about what I was going to bring up about how funny it was. The, The, The. The attempted murder of my character, is, like, amazingly funny, I thought. I mean, it’s almost flapstick.

Libby: Very funny. And let me just digress for a second about that. Alberto, he wrote a play before Uncle Vanya that became Uncle Vanya. It’s called the Wood Demon. Yes. And in that play, the character actually shoots a person, kills a person.

Alberto: Good God.

Libby: Chekhov got rid of all of the.

Alberto: I don’t remember that. Yeah, that was way back in the 80s.

Libby: Chekhov got rid of all of the melodrama and all of the monstrous activity and made it funny. He missed twice, right? Yeah, twice.

Deidre: Twice.

Libby: Yes.

Alberto: Yeah. And I wanted to say how, gratefully, to an actor, the translation is. It’s like. Oh, I can say this line.

Libby: Thank you. That’s great.

Alberto: Some of the more stilted translations, ah, early 20th century ones.

Libby: No, they’re not good. But we’re grateful for them. They brought Chekhov to the United States and to England. So you have to be grateful for Constance Garnett. It was a hundred years ago, but there we go. Yes.

Sarah: so for me, I really remember this being my least favorite play. And I’m very pleased to have come out of it, with a completely different perspective. This read through, I think what really struck me was, similar to Three Sisters, at least for me. the. The obstacles are simply themselves. You know, like all these characters who are straining at this rope that’s tied around them and holding them back, but the thing on the other end of the rope is also them holding back. And so, you know, as an actor, you’re looking for, well, what. What is the obstacle? And the obstacle is you. And the. This play forces so much personal, introspection on, what are the. It’s very difficult to look at, I think, as an individual. What are the ways in which we simply block ourselves from happiness, from agency, from moving forward in life? And I, again, the first time I read Vanya, I was like, oh, this is depressing and sad. And this time I went, oh, my God, this is. Every single character has a slightly different way in which they are exploring this one theme of you are your own biggest obstacle. And I found it a fascinating character analysis.

Libby: Can you give any examples of that, Sarah? I agree with you entirely.

Sarah: Yeah, well, I think looking at Vanya, for example, he is so upset at the professor for having stolen his life from him. But when you have that big blow up scene, the professor says, you could have raised your salary at any point. I just, I didn’t. I didn’t know. I had no idea. So there was nothing getting in the way of him, you know, improving upon his life. It’s just everybody has, you know, these set expectations of how they think something should be happening when in reality it’s in their head. I think, Yelena is similar in that way. I read through it twice. I was looking for what is the thing that keeps her from taking a lover. And it’s never stated. And so I have to come to the conclusion that whatever it is, it’s here.

Libby: It’s not this block is in herself the black. Yes, but don’t you find that it’s true about all of us, that, it’s hard to reveal what we really think?

Sarah: Exactly. Which is why I think this is such an incredible picture, of humanity. And I think that’s what Chekhov does best, and it’s so agonizing. but also, the things that remind us most of ourselves are agonizing. We always hate the people that are just like, you know. So reading to us, I was like, oh, yeah, I’ve got some things to look at.

Libby: They’re exactly like us. Actually, I find it true. I reread, the play this weekend. And, you know, Uncle Vanya, I’ve directed it three times professionally. And so I’ve worked with extraordinary actors, and I’ve known it all my life. and I found myself laughing in new places. And I found myself going, oh, I didn’t get that before. So it’s revealing. It’s constantly revealing. It’s like opening up a, treasure chest and keep going through the layers. At least that’s the way it responds for me. Let me ask you this. Oh, that’s my. I’m not used to technology. You’ll have to forgive me. So if I get buzzes and bumps, I don’t know what’s happening at first. you heard my phone ringing earlier, and I tried to close the doors, as much as I can. But, the cat has to have some freedom to move around. So I have to keep the doors open. But the point is, I don’t know how to turn the phone off. So you have to live with my eccentricities here. And being very old school,

Sarah: I.

Libby: Wanted to ask you, why do you think. I mean, this is a setup with a household of people that go about their business pretty much normally. Vanya and Sonia work the farm, right? And, the professor and his wife come to visit. Like they would visit a. A summer house for a couple of weeks. Normally, you know, it’s a vacation house. and Vanya and Sonia send the money. And the people who live in the house always live in the house. Njania, the nursemaid, has been with them the entire time, of Vanya’s life. so she was there for him when he was a baby. and Vanya’s mother is living there. So the point is it’s a kind of tight household of normal summer visit. Except why is this visit not normal? What do you think is creating, someone said, tension boiling under, sadness going on underneath, what’s going on in the atmosphere that’s creating that. Why does this play happen and peak, in a gun being shot? Any thoughts about that?

Sarah: I have a thought, but I’m excited to hear everybody else’s thoughts. Has the professor just retired? Is this his first year? When he’s gone from being an active member of, academia to non or intelligentsia to retired.

Libby: Yes. So what does that mean?

Sarah: So I feel like, his, status has now been revealed as a nothing burger or a lack of status. And his feelings about that and everybody else’s feelings about that are all spiraling and cooking up this soup of feelings. The purpose that Vanya and Sonja and, what’s the mother’s name?

Libby: Maria.

Sarah: Maria have all been looking up to her is just. It’s deflated. It’s suddenly deflated in front of their eyes.

Libby: Yes. Of course, we don’t know what it is that actually caused Vanya. We don’t know whether he read an article. Article that debuted, the Professor. I don’t think we know exactly what the specific circumstances. So that would be something an actor, Vanya and the professor would need to, to wrestle with, to figure out. Right. But yes, I think that’s excellent, Sarah. he retired. And what did they decide to do when. When they retired?

Sarah: They moved in.

Libby: Right, Moved in. You know, it’s a big difference in coming for two weeks and you’re a kind of popular star, and then you bring all your suitcases and you’re here to stay forever. What does that do?

Alberto: the, short term visits, were probably bearable, but to have to put up with this, professor for and you know, all you can think of, and he’ll be here forever, I think. You know, what is it? Guests and fish start to rot after how many days? And I’m. I’ve been here already how long? I forgot already. since. Not too long. It feels like this time. I mean.

Libby: Yes, I think that’s great.

Alberto: Yeah.

Libby: Any other thoughts about that?

Howard: It’s also like I. I always have this saying of be, careful of working for your heroes because they’ll just come off the pedestal. There’s like, There’s, There’s. They can only come down and it’s like Elena and the Professor. Everybody’s been at kind of this idealized distance forever and suddenly you’re like, you know, they’re. They’re going to be in your face permanently. And it’s like all they can do is lose. Lose value. I think that’s what’s happening. And then this love hexagon, I don’t know what it is, the love Pentagon that’s going on, you know, where everybody’s misplacing. The object of their desire is so rich, you know, I mean, it’s just such an amazing configuration and of course.

Libby: It’S kind of the center of most comedy, isn’t it? Everybody’s in love with the wrong person. it’s how you use those ingredients that makes the difference in, in the kind of play. But that ingredient is really at the center, being in love with the wrong person. how about the fact of, Yelena’s extreme beauty? What do you think about that and what has that got to do with the play?

Deidre: I think, you know, there’s a part of me that feels like there’s.

Libby: Like.

Deidre: It turns up, the feelings of inadequacy.

Deidre: It turns up, you know, I mean, everyone’s just doing what they need to do. And it’s dangling. It’s dangling something that is, irretrievable or it’s like dangling a carrot that’s always going to be dangled and that no one can find any satisfaction out of. And that, you know, definitely for Sonia, you know, I think her devotion and her, you know, her duty, has been the thing that has. And her caring has been the thing that has moved her forward. And now, you know, here’s something that she can’t attain, you know.

Deidre: Sorry.

Sarah: No, no, I. Zoom. Delay. I thought you were done. I didn’t mean to interrupt.

Deidre: No, no, no, no, no, no, no. Go ahead, go ahead.

Sarah: Well, it also, I love everything you just said and it also makes me think, it really sets up the shallowness of beauty, as a commodity. Because everything else that’s said about Yelena is that she’s bored, she is dissatisfied, she’s moving through the life like a sloth. And then you have Sonja. They say she is plain, she says I’m plain. But she is running the farm. She has kept this place alive in every respect. Sonja should be a catch that Astrov, would love. Perfect Match when one will work on Savannah. But because of this beauty with nothing else underneath it, Yelena is still the more desired object.

Libby: In the early 70s, I was lucky enough to see a production of this, at Circle and Square in New York. I don’t even know if that theater still exists, but, George C. Scott, the movie star, played Astro. a very famous English actor by the name of Nicole Williamson played Vanya and Jully Christie. Do you know the name Jully Christie? The movie star of the 70s, 60s and 70s? Well in the beginning, as you know, in the opening scene she played Yelena. And in the opening scene, and I thought, I’m sorry, but in the, you know, Jully Christie, how can she stand next To George C. Scott, this mammoth, incredible actor. And Nicole Williamson. I mean it’s just impossible. Jully Christie, she’s a movie star. She belongs in photo books, not on the stage playing a character like this. Well, as you know, in the opening thing. And it makes me know what a brilliant showman, Chekhov was. The professor and Sonia and Waffles come in from the walk. And they’re walking and trailing behind is Yelena, you know, da da da, da, da, da da, dawdling her way. And Jully Christie walks in in this ivory colored lace dress. And I had, had never in my life seen anything so beautiful. And it makes you. It made me turn away for a moment because she was so beautiful that it’s hard to look at. And I think, I know that sounds strange, but I think I certainly have a lot of Sonya in me. There’s something scared of something that beautiful. She was actually wonderful in the show. But so, haha, Libby, for making judgment before. I should have but that, somebody said very early that the play had to do with longing for beauty. And that beauty is a very, very important part of what’s going on this summer. You know, they’re really looking at her walk across the stage in an ivory dress. Just exquisite.

Sarah: Yeah, it just makes me, think of the way in which Astroph continues to talk about the destruction of beauty in the natural world around them. So it’s like as that’s disappearing, here’s this thing that’s all the more important thing. Person to cling on to if that’s what you’re needing in your life.

Libby: Yes. And yet he remains sexually attracted to her even after she’s rebuffed him and he sees how prim she is. He’s still hoping for a rendezvous in the forest.

Deidre: Well, the beauty also breaks the boredom. You know, it’s like I think the fact that every day is the same year after year after year. And you’ve got this new thing, thing that helps to break up the way you think, the way you move, the way you, you think about life, the perception that you have about what really is beautiful and what really you do yearn for.

Libby: Yeah, yeah, exactly, exactly. I think, I think you have. You’re hitting the heart of the play. Why is this summer different than any other summer? Why didn’t the play happen? Why did Vanya go a little nuts this summer? Thoughts?

Corey: yes, I have, Perhaps age. They mention age quite a bit. And how old. They’re all.

Libby: How old did you see, Corey? How old Is he,

Corey: Vanya’s 47.

Libby: Right.

Corey: and, I mean, I’m not sure how old Sarah Bryakov is. I know astrop’s 37. So they’re all sort of getting older and more unable to do the things that they want to do. And here’s this young beauty in front of everybody. Yeah.

Libby: Yeah. Hard. And he’s longing for her. Vanya.

Sarah: Right.

Libby: He’s longing for her, and he’s not getting anywhere. She’s rebuffing him. And I don’t know. What do you. What do you think? Do you think that he’s been trying to seduce her every year when she comes for two weeks? Or is this new? What’s your sense? Yes, Howard.

Howard: Well, it feels like they’re in a. A pattern, you know, that the, A lot of it is. I mean, what I love about Vanya is. I mean, it feels like a lot of it is teasing. Almost like kind of sibling style. Teasing.

Libby: Yes.

Howard: And, she just sort of elegantly and inelegantly sort of rebuffs it. Like, has figured out how to handle him or how to keep him. How to keep it contained. And maybe this summer, because of the duration of the contact with her, it just. It just keeps building and build.

Nathan Agin: Building.

Howard: Reading your. Reading this translation, one of the things I was really struck by is that this has been going on for now 10 years, right? 10, 12 years. That he’s been pursuing or objectifying her and in love with her. And that Sonia has been going on for six years. You know, these are like these long, long, simmering, unrequited yearnings, you know, that. That all of a sudden, everyone’s like, I’m going to. Okay, I got to make a move now. You know, I got to figure out how I’m going to break this now.

Libby: Why is the now, Howard? What’s the now about it, beside the fact that we’re doing this play? So that’s the now. But why. Why is it happening now?

Howard: I think for Vanya, I think it is the age. having just crossed that threshold, there is this point, where there is a point of a now or neverness. And I think having Astrov as competition. You, know, reading this translation this past couple days, I was like. I was. I was aware that maybe Vanya, even in the first act, is already clocking Astro’s interest. Like, he can see Astro’s interest. And maybe that’s never been, like, there as a spoiler before. And it’s like, well, I better, you know, pardon my French. Or get off the pot here. Because if I don’t, he could. He could sweep, you know, And I think there’s also a sense that the professor may die. You know, that he’s fairly frail and old and, you know, she’s gonna be a widow. And you want to be there to pick that up maybe, like when. When he goes as well, you know. but I think it’s. I think it’s. Maybe it’s the. It’s the contact with. I don’t know. I don’t know how much exposure Astro has had to her in the past. It seems like he maybe wasn’t around as much when she was around.

Libby: He wasn’t around. He says that he. Sonia tells us that he only came once or twice a year and now, there every day.

Howard: Right. And I think his sensitivity is like, what is this? Why is he here?

Libby: And.

Howard: And, you know, you know, men are competitive, so.

Libby: People are competitive.

Howard: Yeah.

Libby: I think there’s even, dare I say, a little competition between Yelena and Sonia. Well, that we can look at at some other point. But. Yeah. Okay, so we’ve got some, male competition because Astroff is there a little bit more. So. Heightens the stakes a little bit. we’ve got 47. And what do you think that means, by the way? Chekhov was dead at 44. So 47 was already for. I mean, it’s very different than the way. I mean, I would say somebody. 47 is pretty young now, but it’s really middle age, don’t you think? I mean, 47 is the middle, hopefully the middle of someone’s life. what does that matter? Why is that important that it’s harped on throughout the play. His age? Anybody have any thoughts about that?

Sarah: Well, I wonder if, it’s linked in with, Vanya’s constant comparison to his brother in law and. And, previously his brother in law was somebody who had, you know, this academia and had this beautiful wife. So two unattainable things. And now that the professor has been revealed as one of these things being completely empty, it’s possible that, the second thing that he has is completely empty as well. So Vanya can’t. Vanya realizes one thing has collapsed. Well, maybe this other thing has collapsed too. Maybe now this is some suddenly unobtainable to me because this guy is just as worthless as I am, therefore, why shouldn’t I have that?

Libby: And he. That’s great, Sarah. And then it’s not just that he’s as worthless, but that he’s the one that I’ve been worshiping. M. Right. And I’ve been, you know, working myself to the bone for. And. And it’s. I don’t know. It’s idolizing somebody all your life, thinking that they’re stars and you’re grateful to be able to serve them, and then discovering that they’re liars and phonies and mean nothing. It’s, I would. I would think that it’s very catastrophic.

Sarah: Yeah. And then when you’re facing your own mortality, you are grasping for some purpose. You’re going, okay, I’m 47. Something has to have mattered that I have done. Let me attempt this. It doesn’t even matter. That’s Yelena. It probably could be another beautiful woman. But there’s just this grasp at purpose from Banya.

Libby: Yes.

Howard: There’s also, like, you know, I’m just a few years older than Vanya, but there’s this, like. There’s this moment right around now where people your age start to die. That is just, You know, I mean, everyone who’s been through it, you know, you’re just like, whoa, that guy is my age, you know, or younger. And that I think, you know, you suddenly go. You suddenly. Are your parents age, you know, or you are your parents. And all of that just kind of. It just catches up with you all at one time. you know, I’ve been like. I’ve always jokingly said, I was. I was kind of a late bloomer in my career in film, in film and tv. And I was like, well, I’m not gonna have time for midlife crisis because I got here too late. But it happens.

Libby: There’s always time for a midlife crisis. But you just said it. Midlife crisis. How does that work with this play?

Howard: I think he’s unmarried. You know, he’s unmarried at 47. And he’s like, if I don’t get married now, I won’t. You know, and that’s.

Libby: And unaccomplished in his own feelings about, What if everything that you’ve been supporting, holding up suddenly appears and Chekhov doesn’t tell us what it is that Vanya sees about the professor’s work. Let’s just do a little imagining here. What could have crashed the idol from high up down to the ground into little pieces? Why. Why would Vanya lose complete faith in the professor, do you think, in this short amount of time? I don’t have an answer for that. I honestly don’t. And that is so individual and actor oriented. Because Chekhov doesn’t even hint at it. Corey. Oops.

Corey: I’m sorry. My light went out really quickly. So what was the question?

Libby: I’m glad it wasn’t me. That’s all.

Howard: I.

Corey: No, no, no. It was my light. Sorry. But, I’m sorry. Can you repeat the question?

Libby: What do you think it is that the professor did that made Vanya just see that he’s a sham?

Corey: I mean, it could be that he’s. It’s just the way he carries himself. Perhaps that he’s. Like.

Howard: He has.

Corey: He’s sick. He’s very sick With. With rheumatism, I think. And he sees that he’s still being himself, his pompous self. And I.

Libby: It.

Corey: Perhaps it was an article like you said earlier, or word of mouth. Maybe someone he went into town and had heard from a local shopkeeper or something that he’s nothing. He’s. He’s written about nothing that nobody else has written about. He’s written about things that other really smart people have already written. So he’s not smart. He’s. Well, not as intelligent as he puts off, I guess. Kind of a sham.

Libby: I think that’s good. Anybody else have any thoughts about that? I. I don’t know the answer. Yes, Jully.

Jully: Going deeper into that. I mean, it sounds like it could have been plagiarism.

Libby: Oh, that’s a fantastic thought. Where.

Jully: Where he’s taking someone else’s words and making it his, own. Which is kind of what he’s doing with Vanya’s life work, right?

Libby: Yes.

Jully: Taking Vanya’s life work and profiting off of it himself.

Libby: Yes, he is. Yes. Deidre, you. You were starting.

Deidre: There’s just, like, the wonder of, like, in trying. You know, it’s like you have an idol, and you try to engage them in. You know, you try to learn what they know. And try to either impress them or engage them in the conversation. Or to gain knowledge and find out that he’s not getting back what he thought he would. He’s not getting. Getting. Getting the responses that he thinks that he would get. He’s not getting the.

Libby: The,

Deidre: Wisdom that he thought that he would receive from this person who is supposed to be so lauded, you know?

Libby: Exactly. And, that’s a pretty big crash. And Vanya, from the minute we meet him very early in the play, remember, first we have the little scene between, Marina and, Astrov. She’s trying to get him to eat something because he’s pacing back and forth. That is my favorite scene because it’s my Jewish grandmother saying, eat, eat something. You will never find that in any other translation. Take a look at other Uncle Von. She’s trying to offer him something to eat. But. But the eat, eat something is definitely from my family. Vanya is. From the first moment he speaks to Astro when he wakes up, he’s absolutely deplores. He absolutely deplores the professor and talks about how his feelings have crashed. and plagiarism is a fantastically interesting idea. in any case, who’s ever playing both Vanya and the professor, and probably everybody there, all of you need to have an idea in your head why the. Why it would be such a tremendous fall into the ground. I don’t know, it would be like somebody telling me or, ah, finding out that Judi Dench really doesn’t even speak. And it’s somebody else’s voice that’s going, you know, somebody that I think is so brilliant and so wonderful. Or that Maggie O’Farrell, who’s my latest passion, you know, didn’t write these books. And so, it all came crashing down. But there’s something there that creates Vanya from the first minute he doesn’t learn it over the play, it’s there from the first minute the play begins that he’s crashed. His idol has fallen at his feet. And if you’ve spent your whole life supporting that idol and doing everything for that idol, and that idol crashes at your feet, that’s a pretty big blow to your life. And if you’re 47, it’s a very big blow because there’s not a lot to change after that.

Deidre: But maybe it’s also. Sorry, maybe it’s also seeing that here’s this woman that you have that you love. You only see them for two weeks at a time, so you’re not really able to see. See the interaction that happens. And so when you see this interest that you have, this love that you have, this yearning, and you see that she’s not receiving the attention and the love that you expect that she should get, and you’re not able to give that to her and she’s tied in with someone else. That also breeds. Like, why him? You know, what does he have that I don’t? You know? And so, like that. That’s a cancer in itself.

Libby: Yes, absolutely. You’re absolutely right. And so you see that these two figures who have decided to live there until the third act, the professor, says that they’re going to sell, these two, the beautiful, exquisite, almost impossible to look at because she’s so beautiful. and the idol of the academic world who turns out to be a phony or whatever. It all comes together this summer when he’s 47 years old. And at 47, living on a farm. What are his opportunities of anything else happening in his life? Alison, can you share what do you think his job opportunities are life opportunities for Vanya?

Alison: Oh, I think, I mean, Russia in this time was pretty calcified in terms of roles and the way that you’re born into a kind of caste system in a way, and you don’t generally leave it. Like you can’t, you know, you usually can’t aspire to like, be a self made man. I mean, maybe that’s possible, but there’s, but not in the rural part of Russia where this is not for somebody who’s older, not for somebody who, you know, whose level of education is what it, is what it is. There’s not the sense of, like, upward mobility where, like, if you just work hard enough, you can be anything. Like that idea doesn’t exist at all in Russia at this time. Like at all. Unheard of.

Libby: That’s great, Alison. That’s very helpful and very true. So that’s another thing. Remember, the play is called Uncle Vanya. Everybody’s yearning and everybody’s lost, but the play is called Uncle Vanya. Dadya. Vanya. Right. God, Giovanna, I love that. he doesn’t have very many options. And if everything that you want and have worked for becomes a soap bubble. Do you remember when he says, oh, it’s an arsene. I won’t even talk about that now. okay, so we have a beautiful woman who won’t act upon her own desires, but only provokes everybody else’s desires coming, to stay permanently. And we have a phony professor who. And, I think all of us that have ever done anything in academia have met the professor by before. You know, that guy that takes over a meeting and has, pronouncements, about everything and opinions about everything. when those two come, it’s like, the summer of the locusts or the forest fires or. It’s the event. The event in this play is not the shooting. It’s that these two people have come to stay and they have created, all of this panic and pain from everybody there. Does that make sense to you? It’s such a subtle thing that that’s what creates it. You need to know, and maybe Allison, you know a little bit about this, the theater of Chekhov’s time was melodramatic, not realistic. Right. Alison, do you have any thoughts about. I mean, Chekhov was taking seemingly quiet, ordinary events and making.

Alison: Well, he was taking normal domestic events and making them interesting, as opposed to putting extraordinary events onto domestic situations.

Libby: Yes.

Alison: You know, and so, like, the melodrama comes out of the desperation and the earnestness of the characters and what a normal person is willing to do under extraordinary conditions, as opposed to the opposite, which is so often historically true in theater, you know, that, like, in classical theater, it’s always like, extraordinary people, you know, meeting with even more extraordinary circumstances. But with Chekhov, you know, it’s a normal person who is just experiencing unrequited love. And that’s the stuff of drama.

Libby: Yes, exactly right. Yes. And so it’s groundbreaking in its own time, but it’s even groundbreaking now. Although I do have to say I realize that, situational comedies are not about extraordinary families and friendships. They’re about ordinary. So I think we’ve learned a lot from Chekhov’s theater. Chekhov was the base for an awful lot of writers and playwrights. and that was known. But here’s this kind of ordinary event of people coming and staying longer, and the whole world crashes. What else do you see going on in the play? what other things are there for you? Somebody talked a little bit about, the environmental. What do you think about that? was Chekhov preaching? I mean, what do you think about Astrov’s views about, the environment and the wastefulness? It seems.

Sarah: I’m not an expert, but it seems like it must have been, a common theme being discussed at the time. Because doesn’t, Lenin and Anna Karenina also focus on the environment quite a bit?

Libby: Levin is Levin. Thank you. Yeah.

Sarah: Not Lenin.

Libby: Lenin had a different environment.

Sarah: So I don’t have an answer. It’s a bigger question. Is. It makes me wonder. This seems to be a big discourse that was happening amongst, at least the educated in Russia at the time.

Libby: I think Tolstoy. Yes, absolutely everything was a boil in Russia at the time. this play was what, 1899 and 1905 was the first of the big revolutions. 1917 is the big one, but 1905 was almost as big. And the revolutionaries, were seething about the czar and the way the country was run, always for hundreds of years. So all of that was going on. Yes. Tolstoy felt that going back into the peasantry, going back to the earth, making yourself in tune with the Earth was a way of finding your spiritual side. And developing yourself as a human being. I think we understand that, and a lot of us feel similarly in the world that we live in. But astro is not 11. He’s not. That’s not what it’s about for him. What do you think it’s about for him? He talks an awful lot. and he doesn’t just talk to Jelena when he’s trying to seduce her, in a way, with his drawings. But, he talks almost right from the beginning. He talks about what’s happening to the forests and the animals. What do you think that’s about for him?

Corey: well, I think maybe since he’s a doctor, he’s, trying to heal something. And probably try to heal something about himself as well in that way. I don’t know. He sees.

Howard: I,

Corey: Mean, he talks about this constant beauty in the forest. And that’s where you’ll find beauty. And then everything’s crashing down. And then Yelena’s beauty is also being wasted. It’s a sedentary lifestyle, just being wasted. The world’s being wasted. And.

Libby: Yeah, that’s great waste. Big, big question in this, In this play, isn’t it?

Howard: Oh, sorry. No, you go ahead with Astro. One of the things, like Chekhov himself, you know, who was, at least in my understanding, traveled a lot. Chekhov. And was traveling all over Russia by train. And as a doctor, you’re different than Vanya and Sonia. Sitting in a house surrounded by the same world, day in and out. He’s like. I mean, Astroff talks about to get to their house is 20 miles. And you get this sense that he’s a person constantly kind of moving around. With this kind of Chekhovian, detached, observational eye. That he’s just seeing the countryside over these two decades disintegrate, you know. And you read about Chekhov making those. Like, didn’t he travel to the very far east of Russia?

Libby: The island. That’s right.

Nathan Agin: Yeah.

Alison: Partially by courage, which is, like, insane.

Libby: Yes. He was ill at the time. He. He wanted to see it. And it was after wood demon crashed for him. So, you know, he made that.

Howard: Yeah, but just. Just the sense of. He’s like. He’s not. He’s just. He’s seeing things and describing what he’s seeing. The trees are disappearing.

Libby: He’s stuck there. He can’t seem to move. This is. He’s very. Well, he’s a country doctor. Right, Astrov. And, he has to travel to people. And he sees the worst of poverty and the worst of, unfulfilled lives all the time. And he’s found a way to, guard against it by falling in with nature, which is pretty spectacular.

Sarah: Yes, Sarah, he’s also. He’s answering in his attempt to keep the forest the thing that is impossible for him as a doctor. As a doctor, you are fighting a losing battle permanently, because we’re all going to die. But the forest can continue on. You know, the land can continue on. Nature can endure if you take care of it, unlike human beings. And so it’s this. It’s like this unsatisfied thing in his doctor’s life that he’s attempting to resolve on the land itself. Yeah, he has that huge monologue about that. You know, he’s so fixated on that man who died on his operating table. He can’t solve that, but he can solve the forest. If.

Libby: What do you think about that fixation? about the man that was dying on the operating, table. And I don’t know whether, Deirdre, you remember, but, Chebu Tikin tells you the story, Irina, the story about the man dying on the table, which traumatized him. And he was a pretty guarded guy who didn’t let much in except liquor. so this obviously had a, painful m meaning for Chekhov. Sarah, I interrupted you. What do you think about that man?

Sarah: Oh, that’s as far as I had gotten. I mean, I think that man, serves in contrast to, like. It’s just this clear example of he cannot, no matter what he does, he cannot prevent death ultimately, but he can help the forest endure long past his own life.

Libby: But as you said, it’s interesting to me because I think it’s a little bit of a mystery, and it’s a joyful thing, which I think, Corey, I think you’ll have fun trying to figure out is why this bothered. I mean, he sees death every day. Why did this man on the operating table who died under anesthetic, why is it so touching to him? It is true that Chekhov, was a doctor. He paid his way through med school in Moscow by writing stories and became very famous in his time. Actually. He was a very well known, and celebrated author of short stories. And he took risk writing plays. But, he, was a doctor. And that’s so key, isn’t it, to the kind of objective, scientific attitude that he sees in people? I know we’re going to say how awful the professor is and what a she is and so difficult, but that’s not what Chekhov is saying. we’ll explore all that as we work through the characters in the play. But the fact that he was a physician is so key to his attitude about all of these things that are happening to these people. He sees it with a dispassionate eye, but tells the truth. Okay, what. What else I. What I’m trying to do tonight? Let me. Let me give you an overview of the way I’m looking at this. we will start next Monday with reading our scene. It’s actually a long. It’s more than one scene. It’s a few pieces. And. And Nathan and I had some fun trying to figure, out how many pages we were allowed to go because of timing on it, of course. I wanted to do the whole second act, because those last couple of scenes are pretty spectacular with the two girls and the two guys, and the guy and the girl. but anyway, we’ll start by reading our scene. and then we’ll go back through line by line and figure out what people are thinking and why they’re thinking it and how that’s put together. So we’re going to take it apart in a way that you never have enough time in rehearsals to do. You always wish that you could do that at the table. and then, at the end of the evening next week, we’ll read it again and then go back. And no matter how short, how little we get through, we’ll always read and then read again at the end, so that the. The play will continue to flower with your discoveries and my discoveries of what’s going on. But I want to. But tonight I wanted this to be. And it is about, kind of the big themes, the theme that the play is based upon and, the themes that are operating through these characters. Have you got any further thoughts about that? Let, me outline for you what we’ve been talking about. We’ve been talking about middle age crisis. Right. We’ve been talking about the destruction of the environment. We’ve been talking about the impermanence, if you will, of beauty. and the longing for beauty. Someone said that very early. and feeling dissatisfied with your life. Middle. Middle age crisis. And what’s the weather, Alison?

Alison: Oh, it’s summer. And there is a storm coming.

Libby: The storm coming. He does use some theatrical devices. Yes. And what happens in a climate like that when a storm is coming? What’s the air like?

Alison: so it’s very humid, actually, and very hot. And when the wind starts up With a storm, you can actually go on YouTube. I was finding all of this footage of. Of a couple different storms that hit Moscow in the last, like, five years or so. And, Melychovo, ah, which is, Chekhov’s estate, which is 40 miles outside of Moscow. So it’s like, pretty much the same climate. Like these storms in Moscow. You can see, like, parts of buildings flying off and, like, the canvas cover of a tennis pavilion, like, coming up and flying off. So unbelievably dramatic, very chaotic. It’s not like a. Oh, is it raining? You know, like a romantic, like, light kind of storm. It’s like a run, run, get shelter kind of storm.

Libby: Yeah.

Alison: So I would recommend looking around online to actually see the footage of it. And you can see the volume of the rain and stuff. It’s like what many of us would think of as, like, a monsoon or something, you know, like an extraordinary, you know, because it’s a fertile landscape. And so, of course, it’s gonna be this, like, you know, green landscape with these storms that blow in of thunder and lightning and aliveness and the.

Libby: And the air is very heavy and very heavy.

Alison: Like, I mean, especially those of you, who have experienced the east coast, like the mid Atlantic, you know, up through New England. That’s a. It’s a particular kind of summer. Like, heavy.

Libby: Yes, exactly. Yes. So the storm is coming, and we’ve, got midlife, crisis happening in the middle of it, which is the storm, really. One of the other things that strikes me that I wanted to, share with you is this sense of nervous breakdown or nerves that are exposed or raw. Ah. Where do you see that? And how do you think that affects the whole thing? Anybody have any thoughts about that? Nerves.

Deidre: You know, you definitely see it with, Jelena and Sonia. You see that in there. You know, Sonia’s just. She’s nervous and she, you know, she needs to talk, but she, you know, she’s, afraid of the truth being told, and she’s afraid of showing her heart, and she’s afraid of. Of, the fact that she’s not going to be, you know, that she’s not beautiful. And so you just. You sense the tension between her and Yelena and the fact that they want to make up, but they, you know, they want to be friends. And there’s that struggle in that relationship. yes.

Deidre: What I thought was really interesting not to leave this. But what I think was really interesting is right at the end, where it almost feels like the end of the storm, you know, it just. It all kind of gets pedestrian in.

Libby: A way, at the end of the play. Yeah.

Deidre: You know, even though there’s all this stuff bubbling underneath. I mean, everything that’s happened, but they’re like, you know, getting their figures together, you know, counting out the number, the covers that they. Back to.

Libby: Yeah. Yeah, but then. But then you have. Yeah. And that. What do you make of that? Why do you think that happens? I mean, when. When there’s big stuff happening in a play and big crisis, nobody goes back to normal. Somebody dies, somebody. You know, things happen. What do you. What do you make of the fact that this goes back to. Well, you’ll get the same amount as I’ve always given you. And scratching of the pens and the reading, of the pamphlets.

Deidre: I mean, there’s a part of me that feels like there’s just. There’s comfort even in the boredom. There’s comfort in the familiar. In the familiar. Like, you know, let’s just. Let’s just. Let’s just go back to zero again. You know. Let’s just go back to what’s comfortable.

Libby: safe.

Deidre: Yeah.

Sarah: Yeah.

Deidre: But I don’t want to change the topic because you were.

Libby: You were talking about the war nerves. No, I like what you’re saying too. I want us to examine these larger things. I think it’s kind of daring of Chekhov, to let things go back to. In quotes, normal. When nothing is normal anymore. Everything’s been exposed. Astrav is not allowed to come anymore. This is tiny, but it doesn’t occur in our scenes, so I’ll mention it to you. Astrov is a drinker, which is very, very common. And especially in a rural life where there’s very little entertainment, or fun. And drinking vodka is what you do. So he’s a big drinker. And Sonia. Oh, that is in our scene, isn’t it? Sonia begs him. Yeah. Well, do you remember in the end, in the fourth act, Deidre, Nanya offers him a drink. And he has promised her that he’ll never drink.

Deidre: And he does.

Libby: And he does.

Deidre: Yeah.

Libby: I mean, to me, that little touch of, He promised her he’d never do it again. And then it just happens at the end. I mean, it’s. Here’s what I want to say. Here’s what I kind of want to have you think about a little bit. Chekhov is like the painter Monet or any of the Impressionists in that he will take different colors to make one color. And he will daub different colors and different textures. That you don’t know what it is when you’re standing up close to it. Because it looks like it’s mushy paint and funny colors. And when you step back, it’s a beautiful lady in a poppy field. Or whatever it is. Clouds coming over. He. He daubs his canvas with little actions. Don’t drink anymore. Then nothing is made of it. She doesn’t say to him in the fourth act, why are you drinking? Nothing. We just have to notice that he’s drinking again. All of the actions are ordinary and expected and put together. They tell you what’s really going on inside these human beings. So for me, these are very great paintings or great works of art. That it takes very close looking at. Before you, can get the whole picture. You have to stand back. But you also have to examine all of the different colors. That make blue. Make a sky or make a lake. That’s the journey for the actor to find the behaviors. The ordinary thing that Things that people do. Vanya is a very ordinary guy. You know, he spent his life working this farm. He’s not a farmer, per se. He’s kind of a manager. But he’s not stupid. He has had some education. His mother reads political and critical pamphlets. These are not people who have not had any opportunities. It’s a surprising and interesting view of a group of people. Without them being melodramatic or special in any way. Except one is unbelievably beautiful. And before this, I don’t know that Sonia worried about her beauty. It was only until she was able to let out that she was in love with Astrov. I mean, it’s a hot summer night with a storm coming. That’s what’s happening in this play. Do you have any other thoughts?

Sarah: I have one other thought. which is just that we haven’t talked yet. About, the professor’s first wife. And how that might be playing into Vanya’s psyche as well. As far as he lost his beloved sister. Is there an impulse to save Yelena. As a way to make up for the fact that his sister is gone?

Libby: I think that’s great thought. I don’t know. What do you think, Howard? Do you have a sense, in that it’s interesting.

Howard: Like what, Allison was talking about earlier. That there’s no social mobility. And this will all come back to the professor. But it seems like for the sister. For my sister to marry. The professor was upwardly mobile. Correct.

Alberto: He’s.

Libby: Well, he’s an academic star.

Howard: But he’s in a Higher. He’s in a higher cast. And we sort of had to buy our way into that. And that was the, you know, that was the, like, star staking the farm on getting. Making this change for her and for all of us, probably. Right. That was going to lift all of our boats. And then it didn’t. And then. And then this trophy wife, for lack of a better word, comes along and. And it’s like. And he. And I meet her at this young impression. I love that speech where he says, I could have married her, you know, that the. That it’s all part of his fantasy or his, delusion, I guess, that he could have been this academic. He could have been the professor he could have married.

Libby: He could have been Dostoevsky.

Howard: He could have been. Right, he says that.

Libby: Right.

Howard: I could have been. I could have been Dostoevsky.

Libby: and Nietzsche. Schopenhauer. Who is it?

Howard: Schopenhauer. Yeah, yeah, I could have been Schopenhauer.

Libby: Dostoevsky.

Howard: that she’s, like, all part of this wrapped up in this fantasy of changing who I am. Like, I think that’s what Vanya constantly has, is this fantasy of, like, I can become somebody. I can just by saying so, I can be somebody else. And then constantly having that pushback in his face. So, all of that’s relative to Giulayda somehow, I guess.

Libby: No, no, no, it is, it is.

Howard: She’s part of the fantasy. I could have that. I could have that sophisticated, conservatory, educated, beautiful, princess. And just as. Just as much as she’s a. She’s a possession in some ways, I think, to find his fantasy and do.

Libby: Do. That’s a terrific word to use because do you remember a woman’s place was as a possession to their husband. Aren’t they still. Maybe not, no. But that’s great.

Sarah: And there’s that. I, can’t remember the details, but he says something about the fact that his sister died taking care of the professor. Like she wore herself down to the ground in order to keep him elevated. That is the final result of helping this guy.